Think of NGOs and the mental image is usually of hard-at-work, dedicated people doing all they can to alleviate the suffering of others – animals, plants, environment and fellow humans. One usually doesn’t associate NGOs with divisive concepts such as religion. Secularism is key, and so is the idea that altruism should stem from basic human values. This premise is misleading though, since we know that religion plays a huge role in most societies and is one of the major reasons why people feel the need to ‘make the world a better place’. Despite the growing number of atheists and agnostics alike, religion still remains the opium and the hangover cure of the masses.

Whatever one’s personal opinion, religion is a powerful force, capable of shaping people’s thoughts, opinions and actions, and mobilising them at a moment’s notice. These characteristics make it ripe to be harnessed by societal and political forces. The Evangelical right in the US, the Pope, the famous Pentecostal movement in Latin America, the rise of extremists in Islam who rule over vast tracts of land, and the RSS, which is the de facto governing body of the world’s largest democracy – all of these are testament to the steady clout of religion (although the heydays of the Church ruling Western Europe or peak Brahmanism are pretty much over, thankfully).

Core principles of religious NGOs

With increasing globalisation and tenets of secularism and democracy spreading far and wide, religious organisations were canny enough to adapt to the new normal. While setting up places of worship and conducting prayer sermons and ceremonies were fine, to remain truly relevant in a world where science and logic were rapidly racking up followers, religious groups realised that humanitarian work was essential. What better way to remain true to the gospel of charity and compassion”two values that are common to all religions”while still commanding the loyalty of its followers. Contrary to the rights-based origin of the secular NGOs, religious NGOs derive their strength and legitimacy from the faiths of their members and followers, believing that it is their duty to serve a divine being and help their fellow human beings – this, therefore, finds an expression in their actions for social and human development.

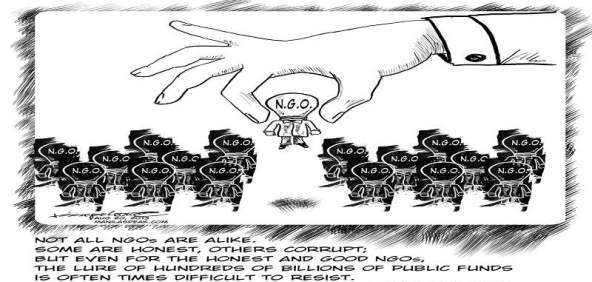

Religion-based NGOs – or faith-based organisations (FBOs), as they are sometimes called – have become ubiquitous in the past few decades. Some of the well-known international ones are Caritas, International Islamic Charitable Organisation, Salvation Army, and World Vision. Many such NGOs are more local to the country of their origin. In many places where traditional non-faith-based NGOs have failed, these NGOs have played a vital role in improving livelihoods of people and facilitated community development and participation. In fact, a 2000 study by World Bank (WB), Voices of the Poor, stated that many people tend to have more confidence in these NGOs rather than secular or government-promoted ones. It helped that top-down, donor-based approaches favoured by large organisations like WB, Ford Foundation and Gates Foundation have been roundly criticised by various civil society groups as well as the recipients of their largesse. Government-assisted NGOs, on the other hand, are often perceived as inefficient and corrupt, at times quite unfairly but first impressions tend to be sticky and long-lasting.

The mushrooming of these religious NGOs is a phenomenon evident across the globe. In 2010, out of the nearly 3,200 international NGOs that had a consultative status at the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), a little more than 300 were categorised as religious by one study, although this figure can vary between 7 per cent and 10 per cent depending on the parameters used. One important characteristic unique to these NGOs is that aside from their humanitarian work, they also indulge a fair bit in religious promotion, asserting that their religion (or at times, religion in general) and their god(s) offer the path to a meaningful life. While they can bring in a much-needed perspective on religious issues that other secular organisations may overlook, they are also known to be quite regressive when it comes to matters like gender equality and alternative sexualities.

Religious NGOs often differentiate themselves with their people-centred approach which works from the bottom up, all-hands-on-deck policy in planning and implementation, and a committed pool of volunteers thanks to their prior standing in the community. Social activism also comes naturally to them. Their firm, ancient roots in the community, ability to regularly collect donations in huge amounts, and a historical affiliation with the poor (though this may be partially disputed) are unrivalled. Many traditional NGOs suffer from their rather detached attitude towards the people that their interventions actually purport to help. Building up credibility within these communities is also a long-drawn-out affair and needs sustained and sizeable investments of time and effort”two things that most people are unwilling or unable to do.

To be sure, there are many who are mighty suspicious or plain contemptuous of these NGOs. The fear is that they are fronts for continuing Western imperialism (especially when it comes to Christian organisations) and/or religious conversion. The latter is an accusation thrown at all such NGOs, irrespective of their affiliation. Not all such concerns are valid, of course, but there is historical precedence to be wary of. Religious people often are zealous about their faiths and can, with or without the mandate of their organisations, seek to spread their beliefs among an unassuming populace. For example, during the tsunami relief work in Indonesia in 2005, there were reports that evangelical Christian groups were trying to spread the Gospel among affected Muslims; it had led to a denunciation by the locals as well as a statement by the Council of Churches in Indonesia to minimise the damage. Similar accusations have been levelled against evangelical NGOs working in Tamil Nadu after the 2004 tsunami.

Christian NGOs in India

Christian NGOs in India

In India, with a majority of the population identifying themselves as religious or spiritual, religion continues to play a significant role in every socio-political aspect of society. This is reflected in the number of religious NGOs that are active in the country. Even though there are no definite numbers, a cursory look at some of the existing NGO databases is enough to validate this assumption.

Interestingly, religious NGOs, aside from raising crores of funds through donors based in India, also get a huge chunk of the foreign donations that are routinely funnelled in for religious causes like education of priests, maintenance of religious institutions and schools, producing and distributing religious literature, etc. As per data released for 2011″12 by the ministry of home affairs, approximately Rs 6,000 crore was received by religious organisations through Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA); out of this, two-thirds were spent on education, training, and maintenance of religious schools, and about Rs 270 crore on explicitly religious activities. In total, about Rs 600 crore was donated for religious causes. To understand the magnitude of this figure, one may note that the government’s expenditure on education for 2012″13 was Rs 400,000 crore, and FDI in 2010 was Rs 1.40 lakh crore.

In the past decade, over Rs 85,000 crore has been donated to NGOs from abroad. Much controversy has ensued over the actual usage of this money. Last year, IT officials found that two-thirds of the 300 organisations listed in the ministry of home affairs website were socio-religious and religious institutions rather than charitable ones. Which is a problem because under FCRA rules, donations for social purposes cannot be used for religious activities.

Christian NGOs have particularly come under the scanner, especially in the recent past. This is in part due to their chequered history of abetting colonialism and conversions during the British rule. While the post-independence era has seen less of such ‘activism’, the taint of being a foreign outpost remains and this is regularly exploited to discredit them. For instance, last year the government blacklisted 30 NGOs engaged in minority welfare from receiving foreign funds under FCRA. Eleven of these were Christian organisations. Then there’s the fact that a significant proportion of the foreign donors mentioned earlier are church-based organisations and their recipients tend to be Christian entities as well. The spectre of forced conversions has also been raised by prominent personalities including Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi, who has gone on record stating that some NGOs funded by international agencies have been carrying out conversions. Here, one must keep in mind that this was published by Panchjanya, an RSS newspaper and hence not exactly a bastion of objectivity. Names like Samaritan’s Purse, Christian Mission Aid, and Partners Worldwide are thrown in to bolster the case against Christian proselytising, even if the actual effect of these organisations may be minimal. Even then, cases like the one where Chennai-based NGO Caruna Bal Vikas came under the IT scanner for diverting funds to Christian religious institutions, rather than investing it for welfare of children, doesn’t help. Fear and scepticism over their political activism and lobbying has also pushed the current government in its brutal”and sometimes overreaching”crackdown on NGOs. Any kind of activism taken up by non-Hindu organisations is viewed as ‘meddling’ in the country’s internal affairs and deemed as a destabilising force. Rights movements, advocacy and agitation are out, while poverty-alleviation schemes are in. It is interesting to note that the current government is mentored (to use a fairly anodyne term) by RSS, which is itself a recipient of these foreign funds. Not surprisingly, RSS did not feature among the 10,000-odd NGOs whose registrations were cancelled under the FCRA. Nor does it face scrutiny for any of its more colourful activities.

Fear and scepticism over their political activism and lobbying has also pushed the current government in its brutal”and sometimes overreaching”crackdown on NGOs. Any kind of activism taken up by non-Hindu organisations is viewed as ‘meddling’ in the country’s internal affairs and deemed as a destabilising force. Rights movements, advocacy and agitation are out, while poverty-alleviation schemes are in. It is interesting to note that the current government is mentored by RSS, which is itself a recipient of these foreign funds. Not surprisingly, RSS did not feature among the 10,000-odd NGOs whose registration was cancelled under the FCRA. Nor does it face scrutiny for any of its more colourful activities.

Last year, a report by the BJP had identified religious conversion by Christian and ‘jihadi’ forces as a serious internal threat. However, for all the dire warnings about Christian groups, the numbers paint a starkly different picture – the percentage of Christians as part of our 1.2 billion population has decreased from 2.6 in 1971 to 2.3 in 2001. Clearly, their nefarious activities haven’t been yielding much result. Even in terms of donations via the FCRA, while the numbers for evangelical and Christian charity organisations have been studied to some depth (one study showed that in 2010″11 they received about 30 per cent of the Rs 11,000 crore foreign contributions), the figures for Hindu and other religious organisations is yet unknown and could potentially be bigger. Reasons enough to ignore that panic button for now and blank out the screeches of Hindutva forces proclaiming otherwise.

The FCRA hypocrisy

It should be noted that foreign donations to NGOs have seen a steady decline since 2014, from Rs 13,115 crore in 2013″14 to Rs 8,756 crore in 2014″15 – a difference of more than 30 per cent. The number of NGOs receiving these funds has also gone down from 22,261 in 2006″07 to 12,014 in 2014″15. Of course, the entire brouhaha over FCRA and foreign donations has not stopped the central government from making tweaks to this Act which are designed to help political parties. Last year, a new rule was proposed to categorise any company registered in India as an ‘Indian company’ irrespective of its shareholding pattern, which, as per current FCRA rules, is limited to companies that have 50 per cent or more Indian shareholders. This minor change will pave the way for increased donations to political parties, who have been charged with accepting foreign funding in the past as well. Like corruption, there’s no shortage of hypocrisy in this country.

Religious NGOs, like many other secular NGOs, have been vocal opponents of projects that undermine the environment and tribal and adivasi rights. The now-infamous IB report of 2014 – which accused foreign-funded NGOs of stalling development and negatively impacting GDP growth by 2 to 3 per cent (!) by opposing mining and other large-scale industrial and infrastructure projects – was another reason (excuse?) for the government to crack down on these NGOs. And the case was stronger for those affiliated to foreign entities like the Catholic Church. Several priests and bishops were named in this damning report, which was severely criticised by prominent individuals and civil society groups.

Interestingly, the IB report failed to mention some of the more famous, home-grown religious/spiritual groups.

The farce of NGOs like Art of Living (AOL), recently made infamous (again) due to the rather pretentiously named World Culture Festival by the Yamuna river in Delhi, is accepted as a commonplace fact. AOL is registered as an NGO and describes itself as an ‘educational and humanitarian movement’, but grandiose delusions aside, it is at best a religious NGO that hardly merits scrutiny by the powers that be despite amassing millions of funds in its various affiliates across the globe. Considering its obvious leanings towards Hinduism, one can wonder if religion-based double standards apply to these NGOs. Many of India’s home-bred spiritual organisations tend to shirk away from the term ‘religious’ but these have an obvious genesis in Hinduism and wield the benefits of being registered as an NGO. Even famous ones like the miracle worker Baba Ramdev’s Patanjali is one, which gives him an extra edge over other FMCGs who don’t get the same tax advantages.

One of the more controversial projects to have been taken up by overzealous Hindu groups is ‘reconversions’. In 2014, months after the BJP came into power at the centre, Ghar Wapsi was launched by these NGOs with the blessings of the RSS. The most famous case was in Agra, where about 300 Muslims were forced to convert to Hinduism by Dharma Jagran Samanvay Vibhag, an offshoot of the RSS and Bajrang Dal. Much hue and cry followed, with Muslim NGOs rapidly gathering in the area in outrage. In all this chaos and its aftermath, what remained constant was the sheer poverty of the victims. As in electoral math, people are just numbers in the game of conversions.

Keeping aside the inanity of the Ghar Wapsi programme, many people have pointed out that hitherto it was Hindu groups who supported strong laws against conversions. While many secular and minority groups are currently opposing this agenda of forced conversions, conversion from Hinduism to other religions does happen. The reasons are manifold and some of them are genuinely understandable (caste system being the biggest issue); yet, that doesn’t change the facts. Islamic organisations are also accused of forced conversions, especially through Love Jihad, due to their religion (like Christianity) being seen as proselytising, unlike Hinduism. The Kerala-based Popular Front of India and Campus Front are some names mentioned in these allegations. Quite a few Muslim NGOs were also under the CBI scanner in 2014. They tend to be more localised, though, in their influence and activities, and hence manage to slip under the radar. And none of them have the outsized influence of the Sangh Parivar.

The largest NGO in India

In this country, no religious or secular NGO holds a candle to the sheer might and influence of the RSS. Candid about its mission to protect the Hindu dharma and bring glory to the Hindu rashtra (secularism be damned), there is a good reason why it is either revered or loathed. RSS’s not-so-glorious history is well known – it refused to participate in the Indian freedom movement, gave rise to Gandhi’s assassinator, openly admired Hitler, was banned a few number of times, rejected the Tricolour and Constitution (of late, it has been trying to portray Ambedkar as some sort of benign Hindutva supporter – clearly, they haven’t read Annihilation of Caste), and in recent times, has been spreading its own twisted definition of what it means to be a ‘nationalist’. A less-known fact is that it is India’s biggest NGO and, by default, India’s largest religious NGO too, with an estimated 2.5 to 6 million members (it helps that there is no formal membership) across at least 40,000 shakhas – the exact numbers are hazy, unlike its right-wing ideology.

Ironically, while its second ban was lifted in 1948 on the condition that it would limit itself to cultural activities, it is now the parent organisation of the central government, spawning many of the ministers that rule (serve?) the nation and is a political powerhouse. BJP is part of the many ideological affiliates of RSS that form the Sangh Parivar, even though some RSS defenders will have you think otherwise despite the overwhelming evidence. After all, both the BJP prime ministers were swayamsevaks, apart from the many ministers and party heads. Even recent state-level party chiefs have been a part of the Sangh. In the UP bypolls earlier this year, ex-RSS member and convict Rampal Singh Pundhir openly boasted about terrorising Muslims in the area.

How RSS became the behemoth that it is now is quite interesting. There are numerous social programmes that it has undertaken which have helped plenty of selected groups of people. Its work during natural disasters, the many schools and relief camps that it has set up, and other charitable contributions are undeniable. However, as pointed out by scholars who have done extensive research on this organisation, it is the provision of basic social services through its sewa wings – notably groups like Sewa Bharati and Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram – to marginalised communities that has expanded the support of RSS beyond its traditional upper-caste Hindu bastion. In terms of organising people with discipline and rigour, few groups can match the prowess of the Sangh Parivar.

Like any other religious NGO, the RSS’s stated aims are social reform and upliftment of the oppressed classes. However, its worldview is shaped by a narrow Hindu-centric idea of what India should be, with non-Hindus required to adapt to it or risk being treated as second-class citizens. Accordingly, its output is moulded by these troublesome ideologies. It must be said, though, that there are certain aspects to its beliefs that are not intrinsically objectionable. For instance, the uniform civil code has merits, even as critics raise doubts on the RSS’s actual reasons for supporting it. For those wary of extreme right-wing posturing, RSS and minority hatred are two sides of the same coin. And this isn’t a baseless fear if history and current actions are anything to go by.

Against the backdrop of the clampdown on foreign money for NGOs, it is fascinating to note that that RSS, too, receives funding from overseas. Presumably, though, the activism and activities of RSS are palatable to this government. A few examples are the Babri Masjid demolition and the following riots, the violence against Christian missionaries and volunteers including the infamous Staines case, the Samjhauta Express bombings (Swami Aseemanand was an RSS activist), the Malegaon bomb blasts, the 2002 Gujarat riots, and the saffronisation of Indian education institutions (the latest of which is an education board exclusively for Vedic sciences, an oxymoron to beat most other oxymorons).

The life and times of the RSS

RSS and its affiliates have been mired in plenty of controversies related to conversions. Year 2014’s infamous Agra conversion case is one example – its regional head Rajeshwar Singh had gone on record stating that RSS spent Rs 50 lakh every month on converting an average of 1,000 families in the area. How much of it was true and how much pure braggadocio is anybody’s guess. A letter from him asking for funds was widely reported in the media – Rs 5 lakh for converting one Muslim family and Rs 2 lakh for a Christian family – the difference in the figures being presumably because Muslims are more devout (or stubborn) than Christians? One of the main reasons why Hindus convert to other religions is caste oppression, an undeniable and shameful fact in India and acknowledged by the RSS as well. A towering figure like Ambedkar himself converted to Buddhism in 1956, and the situation is no better even now for Dalits. While the RSS does provide useful services to these communities, it is still seen as an upper-caste hegemony – all of its sarsanghchalaks have been Brahmins or from a similar caste. Unless this despicable practice is permanently purged from the country, anti-conversion laws will primarily hurt those who suffer most from caste discrimination.

RSS and its affiliates have been mired in plenty of controversies related to conversions. Year 2014’s infamous Agra conversion case is one example – its regional head Rajeshwar Singh had gone on record stating that RSS spent Rs 50 lakh every month on converting an average of 1,000 families in the area. How much of it was true and how much pure braggadocio is anybody’s guess. A letter from him asking for funds was widely reported in the media – Rs 5 lakh for converting one Muslim family and Rs 2 lakh for a Christian family

Numerous such conversion cases have been reported over the years, including in Beawar district of Rajasthan, Kandhamal in Orissa (which left many people dead), Dangs in Gujarat, and Solapur in Maharashtra. The Ghar Wapsi programme was based on the rather convenient view”promoted by its current supremo”that all Indians have Hindu roots and hence every non-Hindu should be brought back into the Hindu fold. Leaving aside the point that the idea of modern India as a nation state is still a legacy of colonial times, this premise is wrong, historically and morally. In its defence, the RSS points out that it supports an anti-conversion law that is not backed by many political groups and so this is proof that anti-RSS rhetoric is unwarranted. Critics counter that the RSS’s agenda here is to merely prevent conversions from Hinduism while keeping out programmes like Ghar Wapsi outside the law’s purview because all Indians originally belong to the Hindu family and, therefore, converting back is not illegal or unethical.

Not much is known of the RSS’s (or that of any of the Sangh Parivar outlets) financials – their donors and exact funding sources are quite hazy. RSS is an unregistered entity; it does not file tax returns and cannot legally receive foreign money, which are astonishing facts about the country’s largest NGO. It operates through its multiple affiliates and trusts, which can be conveniently funded by outside entities. What is known is that the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS), which is the overseas wing of the RSS, is now present in nearly 40 countries (with the United States alone having over 140 shakhas) and millions of dollars from abroad are sent to the Sangh’s coffers every year. These foreign outposts are useful for soliciting donations and the official reasons can be anything – relief work, development, poverty alleviation, etc. According to a 2014 report by South Asia Citizens Web, social and financial support is mobilised by foreign non-profit organisations in the United States, and they include the HSS, Vishwa Hindu Parishad of America (VHPA), Sewa International USA, Overseas Friends of the BJP, and Ekal Vidyalaya Foundation USA, which are sympathetic to the Hindutva ideology and can be considered to be the US equivalent of the RSS, VHP, Sewa Vibhag, and BJP, respectively. From 2001 to 2012, these groups sent a significant proportion of the $55 million funds collected by Sangh-affiliated groups in India.

Such nationalist groups have also started making inroads in the American academia and intelligentsia, specifically in the disciplines of history, religious studies and Indology. Earlier in 2002, another investigation by The Campaign to Stop Funding Hate (TCTSFH) found that 82 per cent of the India Development and Relief Fund (IDRF) donations go to Sangh organisations, out of which 70 per cent is used to spread the Hindutva ideology among tribals. IDRF, which is a US-based charity, received generous donations (about $1.2 million in 2014) from a number of large US companies – Cisco, Sun Microsystems, HP, etc. – by touting itself as a secular organisation working for development and relief work in India. After the revelations by TCTSFH, it wasn’t a huge surprise that one of IDRF’s founders was Bhishma Agnihotri, a well-known RSS ideologue. Defenders will have you believe that it is the small donations of its millions of swayamsevaks that provide the grease to the RSS’s well-oiled machinery. Not many buy this explanation, though. After all, this is the country’s largest NGO.

CB view

While some of the grassroots-level work done by the RSS is laudable and there is much to be admired about its sheer presence and effectiveness, the question remains – at what cost? The Sangh Parivar is not known to fight for people’s rights or civil liberties and doesn’t seem to have any animosity towards neo-liberal policies that tend to hurt the poor and disenfranchised the most”the constituencies it supposedly cares about. Like any group that harbours romantic notions about authoritarianism, with dashes of fascism and hyperbolic nationalism thrown in, it wants ordinary people to follow its righteous diktats and not bother about the finer details or the morality of it all. There’s little to suggest that RSS will ever soften its stance on its core Hindutva ideology. Hence, it becomes equally important to be vigilant and counter its unsavoury designs.

Religion and social work are, by definition, not antagonistic. There is a lot of good that religious organisations have done and continue to do. The problem arises when the concept of ‘good’ is conveniently modified by some individuals in these groups, or by the entire group itself. Forced conversions, unwanted proselytising, and rampant discrimination are unethical no matter how one spins it. Helping people in their quest for a dignified life is commendable; trying to dictate the path they choose in that quest is not. It is imperative that religious NGOs practise what they preach – that all humans are created equal.