The COP24 (Conference of the Parties) will take place in Katowice, Poland, on 3″18 December 2018. This is the United Nations climate-change conference that involves almost every country in the world. The COP is the main decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to combat climate change and global warming. The main focus of COP24 will be to assess the actions taken by the 198 member countries to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as per the commitments made in the Paris Agreement (COP21).

India, being a signatory to the Paris Agreement, had made its own set of commitments, otherwise called nationally determined contributions (NDCs), towards meeting the overall goal of limiting global temperature rise below 2 °C (above pre-industrial levels) and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. India’s main targets are to reduce energy-emissions intensity of GDP by 33″35 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030, and increase the share of non-fossil fuel-energy sources to 40 per cent by 2030. You can read a detailed report on India’s commitments here.

The good news

So, how is India doing on its NDCs? The verdict is mostly positive; the country is on track to meet its targets under the Paris Agreement, which is compatible with the 2 °C limit. In April 2018, the National Electricity Plan (NEP) was released by the Central Electricity Authority (CEA). As per current estimates, the country could achieve the target of 40 per cent non-fossil fuel-energy sources by the end of this year, 12 years before the target year. Some experts have estimated that India will not need any new coal-fired plants for at least a decade, since existing plants are running below 60 per cent of capacity.

The NEP has a core target of 275 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy by 2027.

Data released by the CEA in March this year showed that for the second year running, installations of renewable-energy capacity were more than twice that of net new installations of thermal power. Net thermal addition averaged 6 GW annually, a 70 per cent reduction compared to the previous four years. Thermal power will account for an estimated 42.7 per cent of installed capacity by 2027, down from 66.8 per cent in 2017. An interesting and sensible measure in the NEP is the assumption that hydroelectricity generation will decline by 30 per cent over the next decade because of climate-change impact on monsoon flows.

As per this plan, coal will be used for electricity generation but only to make up the deficit from clean-energy alternatives. A large number of planned coal-fired power plants have already been cancelled, partly due to the fact that the cost of renewables has been dropping steadily over the years, with solar power witnessing a steep drop. In May 2017, the lowest bid for a new solar plant came in at Rs 2.44 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), which made solar power less expensive than coal (Rs 3 per kWH). In fact, 2017 was the first year when renewable-energy investment exceeded fossil fuel-related investment. The government has also announced its plan for electric vehicles to constitute 30 per cent of the total vehicles on road by 2030, a revision from the earlier, highly ambitious goal of 100 per cent.

According to the Carbon Disclosure Project’s (CDP) India Climate Change Report 2017, corporate India has aligned its sustainability goals with those of the NDCs. This information is based on responses from 51 companies including Infosys, Tata Motors, Dalmia Cements, Wipro and Indian Oil Corporation, accounting for 275.92 million tCO2e of GHG emissions.

Nearly 500 units across eight energy-intensive sectors have reduced carbon emissions by 31 million tonnes from 2012 to 2015, through the Perform, Trade, and Achieve (PAT) scheme of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE). This flagship programme is a market-based trading scheme announced in 2008 by the government under its National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency (NMEEE), as part of the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC). It is designed to improve energy efficiency in industries through trading of energy-efficiency certificates in energy-intensive sectors such as aluminium, cement, fertiliser, iron and steel, textiles and thermal power plants. A facility that makes greater energy-consumption reductions than its required targets receives EsCerts, or energy-saving certificates, which can be traded with facilities that are unable to meet their targets, or even stored for future use. Data for the second PAT cycle (2016″19) should hopefully become available next year. In this cycle, the scheme has an overall energy-consumption target of 8.869 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe).

Other climate-related schemes include Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission, dedicated freight corridor (DFC), clean environment cess, Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), renewable energy certificates, and Unnat Jyoti by Affordable LEDs for All. Some like the Solar Mission are progressing better than others such as the clean environment cess.

And the bad

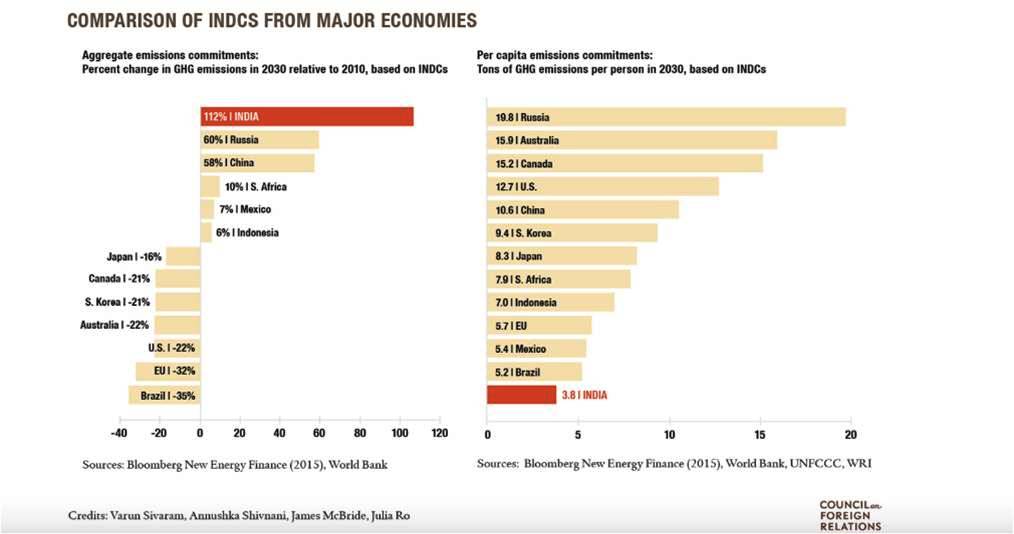

Plenty of critics have pointed out the unavoidable fact that for the world’s third-largest GHG emitter (behind China and the US), India’s NDCs are quite modest in terms of its targets and ambitions. Climate Action Tracker has given India a ‘2 °C compatible’ rating, which means that its climate commitment in 2030 is ‘within the range of what is considered to be a fair share of global effort but is not consistent with the Paris Agreement.’ The agreement requires countries to ensure their efforts result in limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 °C.

India’s NDCs still allow total emissions to rise till 2030, becoming more than double by that year as coal will continue to be used. This is ostensibly because of the fact that the country is still in the developing stage and has millions of people it needs to pull out of poverty. Plus, its per-capita emissions are way lower than those of rich countries such as the US. Even then, if emissions continue to grow unchecked, India’s annual GHG emissions could be the highest in the world by 2050. And with a rapidly growing economy, a continuous rise in GDP means that the country will no longer be able to claim a low per-capita emissions rate.

By 2030, more than three-quarters of India’s electricity will be sourced from fossil fuels and transportation and industry will account for more than half of its emissions – these are sectors where solar and wind power will not reduce emissions. Note that in 2017 coal consumption increased by 4.8 per cent, or 27 MtCO2e.

Moreover, the CEA has revised the latest NEP in favour of coal. The previous version of the NEP did not include any coal-based capacity addition till 2022. In the updated version, instead of retiring coal completely, an additional 6,440 MW thermal power would be needed during 2017″22. This change was a result of feedback from more than 30 state-owned and private institutions. The NEP forecasts that while 48.3 GW of end-of-life plants are expected to close by 2022, another 94.3 GW will be added by 2027. The energy secretary, Ajay Bhalla, has himself admitted that the country will not be able to wean itself off coal until there’s a cheap and efficient way to store renewable energy.

The earlier deadline issued by the ministry of environment, forests and climate change (MoEF) for coal-based power stations to cut down on polluting emissions such as particulate matter (PM10) was 2015. But with most government-owned and private power plants failing to meet this date, the CEA had to come up with a revised plan to retrofit old plants with the required equipment and a new deadline ranging from 2020 to 2024. This is cause for concern because coal dominates the country’s energy mix and if there’s any hope of transitioning to a genuinely low-carbon economy, such power plants will necessarily have to become more efficient and reduce their emissions per unit of energy produced. It is also unclear if all renewables projects will be completed on time and integrated into the grid. There’s also the fact that coal mining is the second largest employer in India and for railways, coal transporting is the most important revenue source. Income from coal royalties constitutes almost 50 per cent of total earnings of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha. The case for coal is economic as well as political.

The government also pushed back a deadline to put thousands of electric government cars on the road by nearly a year as part of the National E-Mobility Programme. State-run Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL) had procured 10,000 e-vehicles in 2017 and was planning to buy 10,000 more in 2018, saving over 5 crore litres of fuel every year and attaining a reduction of over 5.6 lakh tonnes of annual CO2 emissions, as per the government’s own estimates. However, due to a lack of charging points and states being slow in taking deliveries, the first 10,000 vehicles will now be rolled out only by March 2019.

All of this uncertainty around the production and usage of coal has enough experts worried. Then there’s the question mark around decarbonisation policies since one of the NDCs is to reduce the emissions intensity of GDP by 33 per cent”to 35 per cent”by 2030. Progress is slow on the target of creating additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover. As per estimates by MoEF officials, a shortfall of 0.6 to 1.1 billion tonnes is expected by 2030 unless major investments are made. Currently, the average annual increment of carbon stock is 35 million tonnes, which is equivalent to 128.33 million tonnes of CO2.

Then there’s the key matter of expenses. India had repeatedly insisted on funds and resources from rich countries (who are primarily responsible for this climate catastrophe) to mitigate the huge costs of its climate commitments. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was supposed to be a major funding source to poor countries such as India. However, as noted in this report by CauseBecause, contributions to this fund by developed countries has been slow, led by the US which cancelled $2 billion in promised aid to the fund. Of the $10.3 billion pledged, only $3.5 billion has been committed so far and achieving the $100 billion target seems fanciful.

The National Clean Environment Fund (NCEF) has been underutilised and often expanded to other environmental initiatives aside from clean energy. Questions abound on adaptation strategies such as the progress made on programmes like Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (organic farming) and National Initiative on Climate Resilient Agriculture. Without a coherent adaptation policy and robust implementation, there’s a real danger that many of the country’s most vulnerable, indigent people may be left behind in the race against climate change.

India had also set up a Rs 350 crore ($55.6 million) National Adaptation Fund to ‘support concrete adaptation activities which mitigate the adverse effects of climate change’. However, it is yet unclear whether the multiple projects are on track to produce the required results. Union budget allocation has remained around the Rs 110 crore mark in the last three years and total amount sanctioned till February 2018 was Rs 236.32 crore, though disbursal amount is not known. With international financing proving to be unreliable, domestic sources have become extremely important since capacity building in the country’s many states depend not only on funding by the central government but also on the transfer of technology knowhow. Whether the government is up to this task remains to be seen. There are some worrisome trends – since 2015″16, budget allocation for Climate Change Action Plan has seen a major decline.

CB view

Though there’s much to cheer about India’s progress on its NDC, it is important to remember that these are voluntary targets, meaning that the government chose them as per its assessment and convenience. There’s ample evidence that these goals are modest and can be more ambitious to help reach the goal of a temperature rise of no more than 1.5 °C. India is, after all, the world’s largest democracy, soon to become the most populous country, and one of the world’s largest economies. It also has millions of poor people who are at a high risk of climate change-induced disasters. There’s no reason for the country to not strive towards becoming a world leader in clean energy, whilst maintaining its commitment to alleviate poverty and provide better standards of living for its populace. A successful energy transition will necessarily need to balance economic development with social transformation that protects precarious workers. But with the right commitment and planning, this can be achieved.

While current schemes and programmes need to be strengthened and monitored, financing remains a critical issue and needs to be complemented with smart international climate politics as well as correct management of domestic sources such as the coal cess. Climate adaptation is as important as mitigation and the government needs to make it integral to all its efforts.

Simultaneously, India is committed to implementing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To make substantial progress on both NDCs and SDGs, it is imperative that policy goals are aligned as well as close collaboration among institutions encouraged and facilitated. Right now, SDG implementation has been assigned to the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog), the policy think tank of the government and chaired by the Prime Minister, while NDCs are being led and coordinated by the ministry of environment, forests and climate change.

A long-term strategy that looks beyond the current Paris commitments is imperative to realising the country’s long-term ambitions of being a global economic and political powerhouse. This can be achieved not by relying on carbon-intensive mechanisms (as was the case with current superpowers, the US and China) but through clean energy, green living, and zero emissions, all powered by the skills of its populace and state-of-the-art technology. India has to have a robust, long-term view if it wants to thrive in a warming world.

RTI questions sent by CB:

- What %ge of government-owned coal power plants have been able to cut down on emissions and pollutants as required by the ministry of environment, forests and climate change? What %ge of old plants have been retrofitted with new, cleaner equipments?

- What has been the reduction in emissions intensity of GDP to date from 2005 levels, as part of the NDC to reduce the emissions intensity of GDP by 33%”35% by 2030? What was the emissions intensity of GDP in 2005?

- What %ge of carbon sink has been created to meet the target of creating an additional (cumulative) carbon sink of 2.5″3 GtCO2e through additional forest and tree cover by 2030?

- On how many projects are NITI Aayog and the ministry of environment, forests and climate change collaborating, especially with respect to SDGs 6, 7, and 11″15.

- What has been the disbursal (not sanctioned) amount for National Clean Environment Fund and National Adaptation Fund to date?