In March, just before the lockdown started, I managed a visit to Imphal to evaluate if Mary Kom’s boxing academy was doing fine. I had to meet a few kids training under her and maybe predict if the academy had the potential to give India its next Olympian, if not another Mary Kom. Around the same time, my colleague was in Uttarakhand, interacting with Manisha, a cross-country gold medallist (preparing for a national team debut), along with a few other champion athletes at the Khel Mahakumbh. He was trying to assess if there had been any change in the sporting culture at the grassroots and what opportunities could be created for them to climb the ladder.

It’s not that either of us is a sports expert, it’s just that thanks to our ‘common sense’ and social sector experience we had been entrusted with the aforementioned responsibilities by Hero MotoCorp, the company that is supporting the training of budding boxers at Mary Kom’s academy and of more than a hundred sportspersons in Uttarakhand as well as Paralympians. All of this is happening under the project Khelo Hero, the umbrella term for the company’s sports-focused CSR interventions.

For the exhaustive evaluation exercise, we were given direct access to all of their 80 partner organisations (they were all officially informed of our appointment as evaluators), could visit any of their project sites across six states without prior intimation, and could ask for any document. Copies of all their CSR-related agreements, memorandums of understanding (MoUs), the scope-of-work documents (SoWs) and proposals from all partners, along with standard operating procedures (SOPs), were made available to us. All our questionnaires were promptly answered. We even had access to the funds’ utilisation certificates submitted by the project partners.

Team CauseBecause had its task cut out, and that was to evaluate all the programmes and present the company with the true outcomes in terms of social return on investments (SRoI), along with qualitative observations on challenges as well as recommendations and ideas for making the programmes sustainable, scaling them up and working towards achieving a better impact. The brief from the company was clear: Remain independent, objective and fair, and make an unbiased evaluation for us to know if our projects are meeting their hypotheses, are meeting their core objectives, and what value are they adding to society.

In colloquial terms, this sounds cool. However, a study of this scale is not just challenging for its size and scale, but also a task laden with responsibility, as the outcomes of the same will directly impact the lives of thousands of vulnerable communities, in particular, the poor and the marginalised populations living at the edge of poverty in some of the remotest of villages, which one will be hard-pressed to locate on Google Maps.

How Hero fared in the study

My editor allowed me to write this in the first person on the condition that I keep the narrative as short as possible. Hence, I’ve tried jotting down the most interesting outcomes of select projects – in other words, it meant summarising 200-page studies in a few short, crisp and to-the-point sentences.

Education

From developing the necessary infrastructure to getting mobile science labs going, and from remedial and coaching classes to scholarships and other aids for needy students, the programme has a holistic approach towards developing the grassroots education system. As for the impact of these interventions, here are a few key outcomes:

- No girl has dropped out of any of the Hero-supported government schools in Rewari district, Haryana, in the last two years. More so, the overall attendance rates of both students and teachers have gone up manifold. The same was confirmed by the district education authorities.

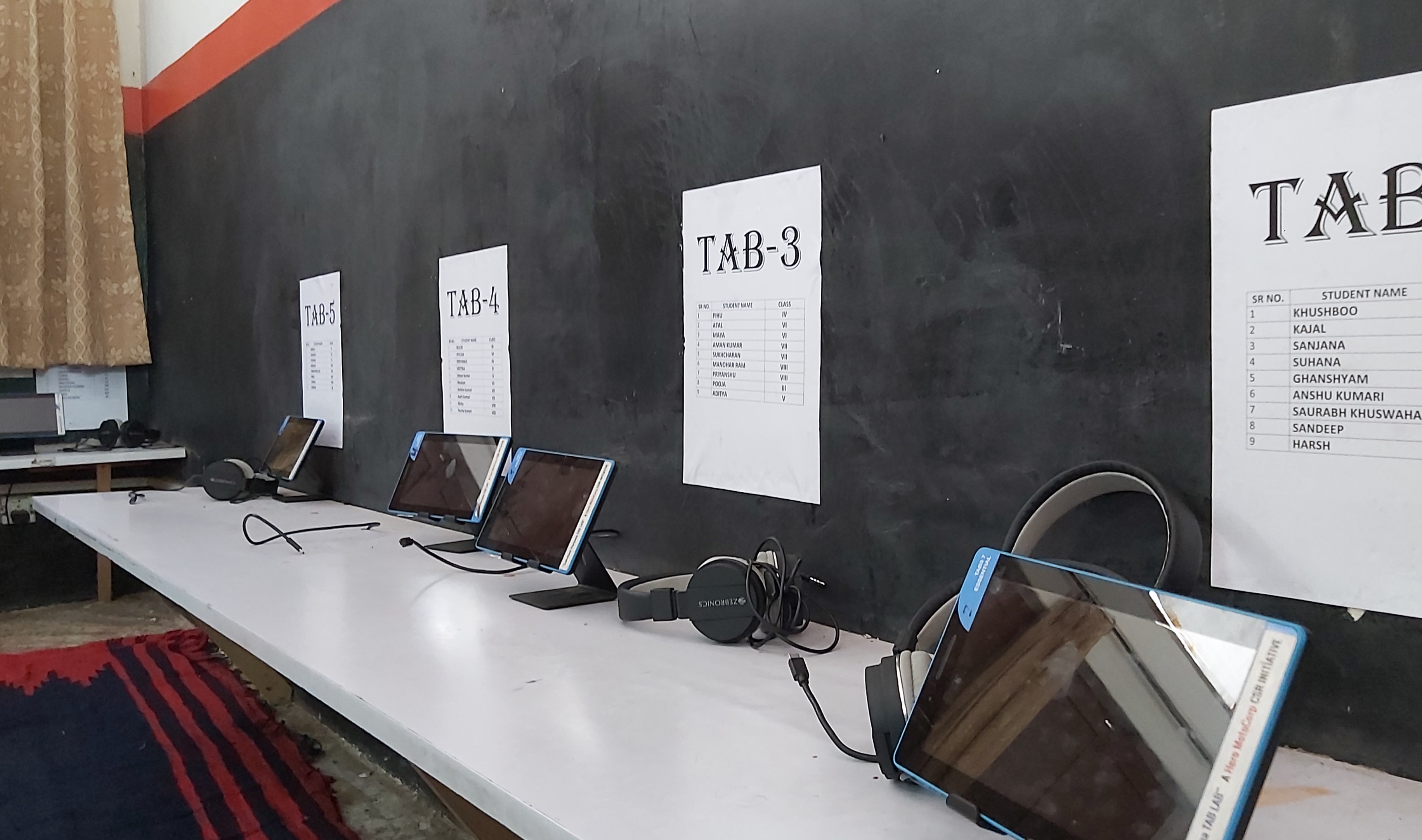

A tablets lab at a government school in Rewari, Haryana

- One may simply drive into any of Hero’s beneficiary schools in the villages in and around Gurugram, Dharuhera, Neemrana, Jaipur and Haridwar. The outlook of the schools in terms of infrastructure and facilities will tell you why villagers are withdrawing their kids from private schools and admitting them into government schools.

- Academically, the number of distinctions received by students in some of the government schools has gone up manifold in Jaipur area, where these students are being given special coaching under the company’s Talent Search programme.

Environment

- With the company surpassing the two million-plus trees mark (it even had its name enter the Asia Book of Records for highest community participation in planting), the evaluation team was all set to carry out its own validation exercise. We had to verify if the saplings planted were alive, and being nurtured and cared for. Applying all possible logic and means – including a tree count – the team concluded that 90% of the trees were alive and about 33 per cent of the same had sufficiently matured to survive on their own. Interestingly, many of the planting sites are being taken care of by community volunteers, who then also get access to quintals of free fruits.

- In over a dozen remote villages in the interiors of the states of Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Gujarat, communities’ stories of how solar streetlights transformed their daily lives made me acutely aware of the privileges that many of us tend to take for granted.

Community members narrating their experiences with regard to the benefits of solar streetlights. At Pali, Rajasthan

For instance, in a few villages around Pali, the menace of wild animals, known to attack infants and cattle, has diminished to a large extent thanks to the installation of the streetlights. A few areas in Haryana notorious for high statistics of late-night thefts are seeing less and less of these crimes. In the uphill villages of Uttarakhand, it is now possible to manoeuvre around the hilly trails after sunset.

Frankly, I had assumed that reading under the streetlight was an old, done-to-death and overhyped tale until I saw children doing their homework under one during load-shedding, which happens often in the rural.

Skilling

While supporting the many skill centres that are coming up in small-town India or paying for skills training for select students is sort of a norm now, with tie-ups with National Skill Development Centres finding mention in almost all CSR reports, Hero’s Centres of Excellence (CoE) caught our attention during evaluation.

- Visit any of the newly formed CoEs by the company and one sees a working model of how even run-down polytechnics and ITIs can be upgraded and transformed into a first-rate training institute. The recently opened CoE exclusively for women two-wheeler technicians, once a men’s bastion, sends out an effective message around gender parity.

- The team was happy to record the personal journeys of many young women working as part of the housekeeping staff in star hotels around Aerocity in Delhi, on the shop floors of leading retail stores or at automobile dealerships… they had passed out from various vocational centres supported by Hero.

Livelihoods

The tried-and-tested model of self-help groups worked quite well for the company in Halol region in Panchmahal district (one of the ‘aspirational districts’ of India, identified as such by the government of India) of Gujarat. Having done the need assessment study in the region about three years ago, I have been visiting the area every year to observe the progress of the SHGs formed by the local NGO with support from Hero MotoCorp.

The enterprising group of SHG members in Halol, Gujarat

To conclude in a line: Two years ago, the women (mostly malnourished) from four village clusters used to be in veils, do household chores, and crib about poverty and hopeless men.

- Today, almost every woman in the area (many of whom I have interacted with during my yearly visits) is a part of an SHG. Many of them are running their own enterprises, making popular Gujarati snacks and handicraft items, trading in saris, organising meals, etc. They also participate in SMCs and panchayat meetings. And yes, their veil is all gone and the success that they have made out of the resources and opportunity made available to them has earned them the respect they deserve from the entire community.

Healthcare

When you have five healthcare vans, one eye check-up van, an eye-care centre and numerous health camps providing free services and medicines to lakhs of poor people, especially those who were out of the government’s healthcare radar, one can very well guess the outcome of the same.

Awaiting their turn to see a doctor at a mobile medical van

- When a doctor at the mobile medical unit in Halol, Gujarat, claimed that every year they treated at least a dozen people with diseases that could have become chronic and even proven to be fatal, we did not know how to add a monetary value to the lives saved while measuring SRoI.

- It was a similar experience when we had the inputs from ophthalmologists managing the eye-care van and the eye-care centre. They have been working on cases of preventable blindness and saved hundreds from going blind. Now, how do you attribute a financial proxy to preventing someone from going blind…

Thoughts

It is not that the programmes of Hero did not face any challenges or that we avoided asking them critical questions concerning the long-term sustainability of programmes; it’s just that after witnessing firsthand the many positive social outcomes and recording so many heart-warming stories (a rarity in the country, you will agree), critics like me can take the liberty of not stressing much upon the improvement areas.

Overall, if at CB we were to rate Hero MotoCorp for its transparency in information sharing, we would give it 10 on 10, and for the overall impact and outcomes of all projects, it would be 9 on 10 based on the simple fact that social value gained as return on investments – along our critical parameters – were beyond expectations, and were at par with the outcomes of some of the best social programmes in the country. Why not grade it 10 on 10 then? Because as far as the social programmes go, outcomes can only get better and that 1 point should ideally be in reserve for that yet-to-be-achieved better outcome.

While the impact and the outcomes of all the projects are noteworthy, it will only be fair to give it 7 out of 10 on sustainability. Why? Because while assessing this aspect, one is always apprehensive if the project will be able to sustain if the supporting company pulls the plug. In Hero’s case, about 70 per cent of their projects have already been adopted by the village communities (viz. SHGs, planting sites, village infra, solar streetlights, etc.) as well as by government schools’ authorities (most education-focused interventions), but interventions like skill centres, remedial classes, healthcare facilities and sports training resources need consistent financial impetus and are yet to reach a self-sustaining stage. Although the long-term sustainability plans that the company has chalked out for such projects are practically sound, these will take a while to fall in place. This is the case with almost all CSR-supported projects across all corporate houses and 7 out of 10 is quite a challenging score – one which many top corporates will be hard-pressed to achieve in the next few years.