‘Nature is pleased with simplicity. And nature is no dummy.’ ~Issac Newton

The recently released annual reports (including sustainability and CSR reports) of some of India’s largest public sector undertakings and large business entities have one thing in common. They all claim commitment to the same vision – to be carbon-neutral by 203o.

But how do they mean to achieve that? Curious as usual, Team CauseBecause reached out to sustainability and CSR decision makers at a few corporate houses to find out what they would do differently and what new interventions they would adopt in order for them to meet their praiseworthy vision. Interestingly, all these leaders have another thing in common. They are all looking at maximising the social, economic and environmental benefits – carbon sequestration to mitigate the company’s footprints – from their CSR investments. Unsurprisingly, many companies at this point are looking at supporting initiatives focused at creation of carbon sinks by following the agroforestry model.

Team CauseBecause spent the last few months delving into researches focused at environment conservation, carbon sequestration, carbon sinks creation, and rejuvenation of forests and biodiversity done by various credible institutions, and also spoke to environmentalists, officials in relevant government departments and sustainability and CSR heads at some of the largest corporate houses in the country.

The insights gained had substantial evidence for us to believe that agroforestry might so far be the best intervention that would give all those sought-after socio-enviro-economic outcomes, not to forget some brand-value brownies, while doing a fair-enough bit for the planet – securing the future of a whopping 9.8 billion of them (or us?) who will be living on Earth in 2050, which is less than 30 years away.

For the benefit of the corporations, institutions and social entities who can, may, and/or must do their bit (and more) towards popularising the agroforestry concept, we are sharing here its 7 direct benefits.

Agroforestry – a simplified introduction for CSR and sustainability professionals

In our experience, the more you read about agroforestry, or the more you talk about it with PhD holders and professors or experts at research organisations, the more complex and daunting the concept may seem. But, take our word for it, it does not have to be that way.

To understand the fundamental concept, one must go back into history”not that far, just about 10,000 years ago. It was the Neolithic era or the New Stone Age when our hunter-gatherer ancestors thought of settling down and grow their own food. They started chopping jungles (which was not a sin at that point of time, just like it is no sin to dig oil today) and started growing wheat, peas, lentils… Ever since, agriculture has continued to play a significant role in human civilisation. It employs a majority of the human population and practically feeds the entire world.

Globally, almost 50 per cent of the land surface suitable for vegetation (forests, for instance) has been converted to agricultural land. About two-thirds out of the agricultural land is used for grazing and one-third for cropland. Most of the current expansion occurs in the tropics, where 80 per cent of all land transformed into agricultural land used to be forested.

It so happened that over time farmers or agricultural communities as well as urban populations started to see forests and agricultural land as two separate parts of the earth. However, this notion is entirely misplaced, because the whole of the agricultural land of today was once a forest of some type. And agroforestry is an attempt to alter the usage of the supposed agricultural land in a way that it can accommodate a bit of forest.

Photo: CIAT

There are three types of agroforestry systems, the most common being the agrisilvicultural systems where crops and trees are combined (such as alley cropping or home gardens). Silvopastoral systems combine forestry and grazing of domesticated animals on pastures, rangelands, or on farms. When all the three elements – trees, animals and crops – are integrated, it is called agro-silvopastoral.

Simply speaking, in agroforestry, shrubs, trees, grasses and bamboos, basically the woody perennials, are grown and nourished along with crops on the same land. This idealistic merger is now being adopted into mainstream farming because of its enormous environmental and socioeconomic benefits. Successful agroforestry models have proven that integrating trees within agricultural systems helps in increased agricultural productivity, reduced hunger and poverty, women’s empowerment, biodiversity support, regenerated soils, enhanced farm resilience, and improved and diversified diets for communities, all of which result in climate-change mitigation.

Interestingly, agroforestry has been recognised by more than 140 countries and has been incorporated in education and training programmes at an unprecedented level since the late 1980s. A survey of educational institutions conducted by The International Council for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF) in 1987 revealed that agroforestry is found as an option for specialisation in undergraduate and postgraduate courses, as well as diploma programmes in forestry, agriculture, natural resources, etc., and many students have also been choosing agroforestry-oriented research projects for their dissertations. All institutions disseminating education in agroforestry have accepted and appreciated its benefits in soil and environment conservation and its capability of combining wood and food production.

The 7 Reasons

1. Combats impact of climate change

Agriculture, land use and forestry are among the large emitters of greenhouse gases. Emissions stem from deforestation, livestock production, and soil and nutrient management. While being a source of emissions, agriculture is also negatively impacted by climate change, resulting for instance in consistently decreasing crop yields.

So, what makes agroforestry a mitigation solution, whereas conventional agriculture is a climate-change driver?

Here’s why: agroforestry unfurls the magic of trees.

Trees on agricultural lands have great carbon mitigation potential. Generally, trees in plains or on agriculture lands are not accounted for when global and national carbon budgets are determined, but are accepted as a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) used to offset emissions from higher-income countries.

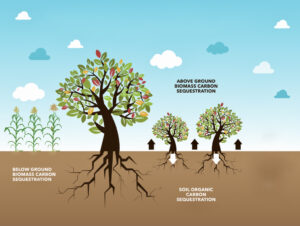

Studies show that agroforestry increases carbon storage not just in above-ground biomass  (that is, stems, branches and foliage) but also below the ground through enhanced root production and organic material from roots and falling leaves and litter that gets incorporated into the soil, thus enhancing its capacity to sequester carbon.

(that is, stems, branches and foliage) but also below the ground through enhanced root production and organic material from roots and falling leaves and litter that gets incorporated into the soil, thus enhancing its capacity to sequester carbon.

Although agroforestry does not store as much carbon as forested areas, it does store more carbon than pastures and fields with annual/seasonal crops. Cautious estimates indicate that agricultural land converted to agroforestry has the potential to annually sequester anywhere from 13.5 tons to 27.2 tons CO2 per hectare, at least for the first 14 years after establishment.

The global mitigation potential, based on the assumption that 20 per cent of the world’s 630 million hectares of unproductive agricultural land is suitable for agroforestry, can be estimated somewhere between 1.7 billion tons and 3.4 billion tonnes per year. Total annual global greenhouse gas emissions in 2016 were estimated at about 51.9 billion.

The graph illustrates land-use systems in the tropics and their potential to store carbon. The bars within each category represent different case studies. Source: Verchot et al. Updated and reproduced by CauseBecause.

A study by researchers at Penn State University has found that in addition to economic benefits, agroforestry could also have a role in mitigating climate change. This is because it sequesters more atmospheric carbon in plants and soil than conventional farming.

During their research, the team analysed data from 53 published studies that monitored changes in soil organic carbon after land had been converted from forest to cropland and from pasture/grassland to agroforestry. They found that while forests sequester around 25 per cent more carbon than any other land use, on average, agroforestry stored notably more carbon than agriculture.

According to the study, apart from the increased storage capacity of the area due to sequestration by trees, the shift from agriculture to agroforestry significantly increases soil organic carbon by 34 per cent on average. Likewise, the conversion from pasture/grassland to agroforestry results in soil organic carbon increase of approximately 10 per cent on average.

Wonder why humans typically are always looking for the biggest, the oldest, the tallest, the greatest. While researching, this writer met with General Sherman, the giant sequoia tree in California.

Measured by volume, General Sherman is the largest tree in the world. Its most recent measurement, at the time of publication, placed it at 276 feet tall, and over 36 feet in diameter at the base. Its circumference – the circular measurement around the base of the trunk – is over 102 feet. Its largest branch has a diameter of almost 7 feet.

Talking of its contribution to the planet, the General is estimated to have sequestered about 1,400 tons of CO2 in its aboveground biomass – more than enough to compensate for one Indian household’s emissions in a lifetime.

The General Sherman was given its name in 1879 by naturalist James Wolverton, who had served under the real General Sherman during the Civil War.

The General Sherman was given its name in 1879 by naturalist James Wolverton, who had served under the real General Sherman during the Civil War.

2. Creates resilience against climate shocks

Agroforestry can buffer climate extremes. It has the potential to absorb the serious shocks that the climate has started to give us all. This system of agriculture gives an opportunity to improve the Earth as also local communities’ resilience against calamities such as droughts and floods.

As agroforestry propagates diverse farming and multiple types of produce – crops and fruits or herbs, it can help reduce the vulnerability of farmers’ livelihoods. Reliance on a single crop, depleting groundwater, diminishing quality of soil, unpredictable rains and storms, and surprise raids by insects (remember the recent locust attack?) are farmers’ major worries – and ours too, because our food is at stake.

Conventional agriculture is often harmful to soil and its productivity. It destroys its living organisms and its sensitive structure, and takes away important nutrients. Yet, soils are essential for human wellbeing. Agroforestry can turn this development around as it can improve and preserve soil conditions. Trees and plants protect soil from flushing or blowing away, while dead plant materials retain water in the soil and nurture living soil organisms. All of those benefits are vital for productive agriculture.

Hardwood trees mixed with conifers planted in and around the farmland also prevent soil erosion, which is a major cause of floods. Trees also improve the micro-climate by shading crops and cooling the surrounding air by increasing the transpiration.

Global warming is steadily increasing the frequency as well as the intensity of extreme weather events such as heat and cold waves, droughts, dust storms, desertification, changing rainfall patterns, flooding, and sea-level rise.

If the warming continues at its current pace, it will adversely impact food security, which might collapse by 2050 and will impact the poor and vulnerable populations across the world, especially in the developing countries including India.

3. Aids in the conservation of biodiversity

While agroforestry is a diverse system in itself, it also supports life in its surroundings. Birds and insects – which strengthen the ecosystem – get diverse food, enhanced shelter and equitable habitat in areas under agroforestry.

In all, the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services estimates that as many as one million species are now at risk of extinction if we don’t act to save them.

The number includes 40 per cent of all amphibian species, 33 per cent of corals, and around 10 per cent of insects.

Likewise, a wheat plantation offers a lot more protection from wind, rain and predators when it is combined with hedges or rows of trees on their boundaries. Moreover, pesticide applications that harm insect populations are reduced or completely abolished in agroforestry.

Agroforestry also restores and maintains the topsoil – the ‘liveliest’ material on earth. In agroforestry, this top layer is covered with dead organic elements such as leaves and pruned branches, which not only protect the soil and keep water from evaporating, but also feed living organisms such as earthworms and other insects that happen to be fodder for birds. Some of these organisms are also a food source for families of rodents such as squirrels and rats, which in turn are prey for larger species. In this way, agroforestry helps balance the ecosystem and adds great value to the natural food chain.

4. Boosts women empowerment

As per Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), women provide 43 per cent of the agricultural labour force in lower- to middle-income countries, but are just representing 13 per cent of the landowners. In general, female farmers are disproportionally affected by climate change, as they have less access to credit, agricultural inputs, and extension services.

For such women, agroforestry can provide many empowerment opportunities. Firstly, agroforestry requires less input than conventional agriculture and can therefore be accessible for female farmers with limited resources and credit.

Women sowing mangrove seeds at Sustainable Green Initiative’s (SGI) project site in Sundarbans

Secondly, agroforestry provides many products that can empower women by freeing up their time. In many regions across India, women and girls are tasked with time-consuming activities like collecting firewood and fodder for animals. When these products become available at the farm, more time can be spent on income-generating activities or education.

Women are frequently responsible for small-stock husbandry and the feeding of larger livestock, particularly milk cows and calves. Thus, agroforestry projects that involve fodder trees, the servicing of crops by trees, or intercropping of crops and trees must include women, since it is often women who grow the crops or care for the livestock that will be involved.

Collecting firewood, animal fodder and fruits is also an important coping mechanism for women during years with low yields. Not surprisingly, studies show that women in general choose to plant trees that increase availability of firewood, animal fodder and fruits, while men tend to focus on fast-growing, timber-producing trees.

Rural women across India bear the major or sole responsibility for food production and account for 43 per cent of agriculture labour force. An FAO study says women’s labour and women’s decision-making are absolutely crucial to agricultural production and development in rural India. Temple murals in northeastern India show women as the ‘first domesticators of plants.

FAO researches say that gender roles are reflected in ownership of trees and associated products. Women tend to benefit from tree products, mostly fruits, with a lower commercial value. The composition and design of an agroforestry system therefore affects opportunities for women’s empowerment.

5. Is good for health

Imagine a monotonous one-crop farm and then compare it to a land where crops are surrounded by varied species of trees, shrubs, herbs, or vegetables, in what is a vibrant illustration of agroforestry. You will agree that a walk through the latter will be a much more fulfilling and invigorating experience than making your way through a standalone mustard field.

Agroforestry gives us a sense of the abundance of life.

Also, as agroforestry replicates nature’s order, the populations living in the vicinity have better health and are at reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases as well as ailments caused by air pollution. More so, if one is also sourcing and consuming the organic produce from there, they are bound to be healthier than their counterparts who get their food from traditional farms.

Studies have also shown that populations living closer to nature, even those who are in urban areas where farmlands are balanced with agroforestry, experience minimal stress and anxiety.

A report by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) says that incidences of poor health are increasing in urbanised societies partly due to expanding urbanisation and modern lifestyles, adding that current healthcare practices alone cannot solve these problems.

The solution is to promote forest environments that help human beings’ psychological and physical rehabilitation.

6. Promotes wellbeing of farm animals and healthier dairy and meat

Agroforestry provides an opportunity for improving the wellbeing of farm animals. In the silvopastoral system of agroforestry, cattle, sheep, or chicken can roam around freely and live out their instincts like they would in the wild. Chickens, for example, are forest animals and feel more comfortable when having the shelter and protection of trees around on their outdoor pastures, and tend to lay more eggs in such conditions. Likewise, domestic animals such as cows and buffaloes are happy moving around freely in green pastures; they also lactate more compared to animals that are tied and kept in enclosures.

Researches have proven that animals that have an active life, enough space to move, and open environments wherein they feel free also produce healthier meats. FAO recommends efficient, experienced and quiet handling of livestock, including taking measures to eliminate pain and reduce stress in the animals and prevent quality deficiencies in meat.

Researches have proven that animals that have an active life, enough space to move, and open environments wherein they feel free also produce healthier meats. FAO recommends efficient, experienced and quiet handling of livestock, including taking measures to eliminate pain and reduce stress in the animals and prevent quality deficiencies in meat.

It is to be noted that animals brought up in the silvopastoral system have a higher glycogen content in their muscles. After the animal is slaughtered, the glycogen in the muscle is converted into lactic acid, and the muscle and carcass become firm due to setting in of rigor mortis. This lactic acid is necessary to produce tender and tasteful meat of good quality and colour. However, if the animal is stressed before and during slaughter, the muscled glycogen is used up and the lactic acid level that develops in the meat after slaughter is reduced, resulting in adverse effects on meat quality.

A report by the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the right to food states that pesticides have “catastrophic impacts on the environment, human health and society as a whole,†including an estimated 200,000 deaths a year from acute poisoning. Pesticides can persist in the environment for decades and pose a global threat to the entire ecological system upon which food production depends.

Excessive use and misuse of pesticides result in contamination of surrounding soil and water sources, causing loss of biodiversity, destroying beneficial insect populations that act as natural enemies of pests, and reducing the nutritional value of food.

7. Acts as a natural pest control

Agroforestry has proven to be an effective preventer of pests that are harmful to precious crops. These could be animals, weeds, or fungi that eat or compete with fruit and vegetable plants. Especially long-lived trees and shrubs such as coffee, cocoa or bananas are less likely to suffer from pests in agroforestry systems.

This is – among other reasons – because agroforestry systems contain more plants and animal species than purely agricultural systems. More insects, birds, and other organisms mean that harmful species face more natural enemies such as predators or competitors that keep their numbers low – it is a natural control system. This way, valuable food crops are naturally protected. Furthermore, harmful weeds have a hard time spreading in an agroforestry system, as they do not cope well with the shade provided by trees.

A thought

Looking at the potential outcomes and impacts, as well as its role in safeguarding the planet and enhancing food security for its people, especially the poor and vulnerable communities, agroforestry is undoubtedly one of the best investments that any socially responsible corporate can be making.

Also, all the companies that are committing to go carbon-neutral know it quite well that there are only limited measures that they can take within their operations. Using more renewable energy, water-efficient processes, green mobility and waste management and recycling practices are needed but may not be enough to mitigate the companies’ overall carbon footprints. They will have to look beyond and engage in planned afforestation or agroforestry and thereby measure the carbon sequestered or the carbon footprints mitigated through agroforestry.

It helps that in the Indian context, agroforestry meets multiple objectives of sections of CSR prescribed in Schedule VII of Companies Act 2013. It is the only intervention that can help companies mitigate carbon while meeting their CSR compliances and also make a positive impact on communities at the grassroots.

A substantial amount of CSR budgets can be reserved for agroforestry interventions for the next few years and a broad plan devised keeping CO sequestration targets with datelines in place. Sustainability and CSR leads may sit together and find out how many and what species of saplings may be planted in which region to be able to achieve the target.

To begin with, identify the villages where you already have multiple ongoing programmes and communities already trust the brand. Conduct a baseline to understand agroforestry potential in the area, engage with the local farmers and make them the primary stakeholders in your interventions, and make it a beneficial proposition for the farmer, the company, the planet, and all of us.

In November 2020, 24 companies aligned themselves with India’s commitment under the Paris Agreement and pledged to support the government in taking India towards the path of lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Representatives of companies such as Tata, Reliance, Mahindra, ITC, ACC, Adani, Dalmia Cement, JSW and Piramal signed a declaration on climate change by voluntarily pledging to move towards ‘carbon neutrality’.

Describing how they would collectively achieve the ‘net zero emission’ goal, the leaders shared nine specific mitigation measures including promotion of renewable energy, enhanced energy efficiency, water-efficient processes, green mobility, planned afforestation and waste management as well as recycling.

Although India, unlike China, the European Union (EU), Japan and South Korea, has so far not committed to ‘net zero emission’ target as its national goal, these companies have stated their intent to voluntarily do so through industry-specific measures.

Team CauseBecause will reach out to these companies to get more details on their plans and strategies – in particular how agroforestry fits in their long-term plans – and will continue to report on their progress in the upcoming issues.

In what is a first for India, carbon pool data (soil carbon stocks, litter and weed biomass carbon) was collated and shared in December 2020. Alongside, information on absorption of

CO2 by mango orchards in the country was also shared.

CO2 by mango orchards in the country was also shared.

The findings, published in a study by the Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR)-Indian Institute Horticultural Research (IIHR), Bengaluru, declared that India was one of the largest carbon-absorbing nations from mango orchards globally and identified carbon sequestration across states that cultivate mango.

India’s mango orchards sequestered 285 million tonnes (mt) of carbon dioxide (CO2) during its lifetime (35″40 years), equivalent to greenhouse gas emissions from sixty million (60,509,554) passenger vehicles driven in a year or CO2 emissions from 73 coal-fired power plants annually.

Quick-read notes

Benefits of agroforestry

- Contributes to achieving at least 9 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- Helps not only in climate change mitigation and adaptation, but also in increasing communities’ resilience to climate-related shocks

- Reduces poverty and hunger through higher yields and more diverse livelihoods for the marginalised

- Preserves biodiversity as trees provide a habitat for multiple species and create landscapes important for their survival and growth

- Improves soil fertility, an important aspect for increasing food security

- Empowers rural women by strengthening their control over natural resources and freeing up their time. For example, instead of gathering firewood, women engage in income-generating activities

Hero MotoCorp and SGI partnership

If you are from Delhi and have managed some memorable walks in its reserved forest areas including Sanjay Van, Tilpath Valley, Sanjay Lake and Okhla Bird Sanctuary, you must have noticed a pleasant gain in their green cover. The barren patches have diminished noticeably. And if you are a keen nature observer or engage in birding, you may have also noticed that some rare species of trees, herbs as well as birds are gradually making a comeback. CauseBecause’s evaluation and assessment teams who have been regularly visiting these areas recorded how little saplings turned into handsome hardwood trees, elegant bushes and prospering conifers, in the process reviving some of the lost forests of the national capital.

If you are from Delhi and have managed some memorable walks in its reserved forest areas including Sanjay Van, Tilpath Valley, Sanjay Lake and Okhla Bird Sanctuary, you must have noticed a pleasant gain in their green cover. The barren patches have diminished noticeably. And if you are a keen nature observer or engage in birding, you may have also noticed that some rare species of trees, herbs as well as birds are gradually making a comeback. CauseBecause’s evaluation and assessment teams who have been regularly visiting these areas recorded how little saplings turned into handsome hardwood trees, elegant bushes and prospering conifers, in the process reviving some of the lost forests of the national capital.

Much of the credit for this laudable turnaround goes to Hero MotoCorp. The world’s largest two-wheeler manufacturer has initiated and invested in multiple environment-focused initiatives over the past decade. Until last year, the company had planted 2.5 million trees and continues to care for all of them. Even the pandemic could not halt the company’s green drive as it managed more than 200,000 saplings (until October 2020) through agroforestry – a model that has been a success so far as outcomes, impacts and economies of scale are concerned.

The model

Hero MotoCorp partnered Sustainable Green Initiative (SGI), a decade-old non-profit entity known for its innovative agroforestry and horticulture models, to add more depth to its planting initiatives. SGI engaged with various district authorities, and eventually received permission from the Deputy Commissioner of Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, for initiating agroforestry projects in the district.

The pilot was initiated in 2018 covering 125 acres (over 50o,000 square metres) of land, of which about 15 acres (60,000 square metre) was public land and rest belonged to small landholders. More than 1,200 farmers engaged in the project and planted more than 51,000 saplings of fruits across their farming fields.

Step-by-step implementation

Step 1. A thorough baseline research is conducted to understand the geography, climatic conditions, soil types, irrigation facilities, ongoing farming practices, and economic feasibilities. The research also focuses on the sociocultural setup and socioeconomic statuses of small landholders and farming communities including farm labour.

Step 2. On the basis of the findings on geographic conditions and market/economic viability, saplings of conifers (especially fruits), hardwood trees and shrubs are shortlisted. An outline map of areas for planting – public land, boundaries of farms and fields, areas within the plant – is drawn.

Step 3. The insights from the baseline research help in engaging with the farming communities. Workshops, confidence-building sessions and group discussions are organised, with focus on generating awareness about the benefits of agroforestry. The openness of the approach helps the team gain the trust and consent of the communities with regard to participating in the project.

Step 4. A nursery is set up to grow and nurture the hybrid saplings in the vicinity of the project site. The benefit of a local nursery is that the saplings do not have to be acclimatised. Consequently, not only do the saplings have a high survival rate, the transport cost and associated carbon footprint are mitigated too, keeping the per-sapling cost considerably low – in fact considerably less than the ones sourced from commercial nurseries.

A nursery in the vicinity can also serve as a resource centre for organic manures and fertilisers as well as a knowledge hub for better farm practices.

Step 5. SGI’s ground teams and the local communities start planting the saplings as per a scientific plan. In subsequent phases, farmers continue to nurture the saplings while SGI’s engagement moves on to monitoring progress, providing guidance, and knowledge-sharing. The team also works with farmers to ensure that essential nurturing activities such as watering, fertilising and pruning are done right and on time.

Outcomes so far

Economic: By November 2020, more than 10,000 hybrid saplings, especially of papaya, guava and banana, had grown into trees and were bearing fruits too. The sale of these fruits ensured value addition of up to 10 per cent on the average annual income of about 300 farmers.

Environmental: While the overall environmental assessment of the project will be done in the middle of 2021, a walk around the fields, talks with the local communities, and before-and-after photographic evidences show that fields that once had single-crop farming are pronouncedly greener and richer today.

Bee farmers in the vicinity have reported a higher yield of honey as their bees did not have to travel far. Elsewhere, farmers reported that the natural shade from the conifers and the organic manure used in farming resulted in better yield of crops and also helped maintain the quality of the topsoil.

Social: The trees around the fields needed additional nurturing hands, so SGI employed the local people, especially women. That translated into additional income for them.

Farmers sharing a part of the produce with farm labour is a usual practice. In this case, apart from regular grain and lentils, the workers received fruits and herbs, making their regular meals nutritious.

Carbon sink: While the natural aboveground carbon mitigation through the saplings planted is yet to be assessed, it can be estimated that 2021 onwards, the project will start sequestering about one million tonne of carbon per year for another 40″50 years.

This project has been independently evaluated by CauseBecause as part of the overall evaluation study of CSR interventions of Hero MotoCorp.