Governments in India may be known for their deep-seated corruption, megalomaniac leaders, and a tendency to divide and rule, but there’s no shortage of big, pompous projects. The Delhi”Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC), part of the current government’s flagship programme Make in India, is one notable example. The other that comes to mind, both for its grandeur and ambiguity, is the interlinking of rivers project (ILRP).

As the name suggests, the project is about linking various Indian rivers through canals and reservoirs to reduce flooding and decrease water shortage. In a country as vast as India, variances in the amount of natural water supply are common (71 per cent of India’s water resources are available to only 36 per cent of land area). So, on the one hand we have places in Assam where rampant flooding due to the overflowing Brahmaputra arrives every year like clockwork, while droughts are common in many water-deficient states like Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Jharkhand.

About ILRP

The basic idea here is to transfer surplus water from rivers like Brahmaputra and Ganga and their tributaries to the parched western and southern states. In all, 37 Himalayan and peninsular rivers will get connected through 30 projects. However, only nine of these are independent linkages, the rest depend on other rivers. For instance, eight other links down south depend on the Mahanadi”Godavari link. An interesting but little-mentioned fact is the State’s definition of ‘surplus’ and ‘deficit’ which factors in only human consumption of water whilst ignoring all other living beings and the environment itself. Also, the mechanisms for deciding the exact quantity of water to be diverted are contentious and prone to subjective biases and convenient assumptions.

At a cost of a whopping Rs 11 lakh crore (that’s 12 big zeros), this is easily the mega project to beat all mega projects. If all 30 projects actually end up being implemented, this will be the biggest water-based infrastructure project in the world, beating China with its over 22,000 large dams (although it is fourth in terms of storage volume). Take a cursory look at the numbers: 3,000 storage structures, a canal network stretching almost 15,000 km and transferring 174 billion litres of water a year, 34 GW of hydroelectric power generated, 87 million acres of land irrigated, and over 500,000 people facing displacement. No surprises for guessing that most of those people will be the already poor and underprivileged.

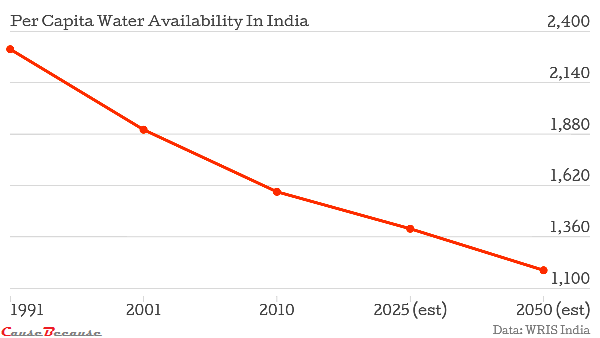

Among the many extreme dichotomies of India, one is the fact that a country that is known for its engineering and IT prowess still depends on something as fickle as the monsoons for its annual crop output. And in a country where a sizeable chunk of the population depends on agriculture for livelihood, that should be inexcusable. With the ever-increasing population, it is estimated that the irrigation potential has to be increased to 160 million hectares for all crops by 2050 – no small task considering that currently that number is around 95 million hectares. Bear in mind that India has nearly 18 per cent of the world’s population but only 4 per cent of its water resources. As per projections by the National Commission of Integrated Water Resources Development (NCIWRD), irrigation will still take the lion’s share of water usage for the foreseeable future (disputed by others). By 2030, the water supply in the country is expected to meet only half of the demand. Add to this the fact that at COP21, India had pledged to harness 40 per cent of its energy needs from non-fossil-based sources. And hence, hydropower projects suddenly seem intensely urgent.

ILRP is spearheaded by the National Water Development Agency (NWDA) under the ministry of water resources and has found a champion in the BJP government after being first mooted in 1982 and then promoted by former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The rationale given for this mega project is threefold: prevent drought and flooding, increase the irrigation potential to increase foodgrain production, and counter regional imbalance in the availability of water, even as this project is likely to alter the geography of the country.

The history of this project can be traced back to the 1970s (or pre-Independence, depending on how far you want to go), drawing support from many governments but failing to gain much traction, until a Supreme Court ruling injected new life into it. In the ’70s, two proposals were made imbibing the core philosophy of river linkage. One by KL Rao received much attention. In 1982, Indira Gandhi set up the NWDA primarily to assess the feasibility of the same. However, it was the Vajpayee government that revived this as one of its flagship programmes and greenlighted the Krishna”Godavari linkage. Before this, in 1999 the NCIWRD modified the proposal from inter-basin to intra-basin transfer, stressing on optimal uses of existing land and water resources. Between 2005 and 2013, a number of committees and reports were commissioned on this project, attempting to resurrect it even as the protests against it grew louder and more urgent. Finally, in 2012 the Supreme Court directed the central government to implement this project by 2016 (which, depending on how you look at it, was incredibly ambitious or unbelievably naïve) and set up a committee to oversee the planning and implementation. Here it should be noted that the judgement was based on one report by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) and the recommendations of a parliamentary standing committee, while ignoring the opposing views of a number of civil society groups and think tanks. The SC judgement was also criticised for judicial overreach as it did not have the authority to prioritise national projects that were under the government’s ambit. Ultimately, it was the newly elected BJP government in 2014 that took this project up two years after the SC directive was issued and formed a task force to reach a consensus among all states.

Why link rivers?

Proponents of the ILRP cite the numerous purported benefits of water transfer. The obvious ones are the mitigation of the annual damage caused by floods in the northern and eastern parts of the country, relief to drought-prone areas, increase in the irrigation potential, improvement in food security, and hydropower generation. Less known are the facilitation of water-based economic activities such as internal navigation, groundwater recharge, and fish farming.

By 2050, the per-capita water availability in India is expected to fall from the present 1,545 cubic metres (2011) to 1,140 cubic metres, way below the accepted thresholds. Then there is the issue of excessive groundwater usage”especially for agriculture”resulting in its steady decrease, the ever-increasing demand by a burgeoning population and industrial sectors, rapid urbanisation, and economic development. These unavoidable factors are only going to exacerbate the pressure on existing water sources and it becomes clear that transformative solutions are urgently needed. Alternate, local solutions are dismissed because of their limited potential, especially in arid and semi-arid regions. Pro-ILRP advocates cite figures that demonstrate the underutilisation of existing water resources such as the Brahmaputra river basin’s renewable water resource being about 584 cubic km, which is around a quarter of India’s total water resources. ILRP is projected to increase the usable surface water by 25 per cent. On environmental concerns, they point out that poverty is often a leading cause of environmental degradation (which the project hopes to minimise) and that examples such as the Bhakra Nangal dam have demonstrated the viability and benefits of large-scale human interventions. Existing precedents like the Western Yamuna canal and Agra canal in India as well as inter-basin transfers in the United States, China, Spain and South Africa are also cited as working examples.

Villagers welcoming river Godavari’s water reaching Prakasam Barrage, the dam on river Krishna at Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh.

Current status and issues

Last year, the Krishna and Godavari rivers were connected through a canal in Andhra Pradesh at a cost of Rs 1,300 crore. The Polavaram dam, still under construction, will eventually be used to divert the water from Godavari. The dam itself has been the subject of much controversy as it will submerge 1.5 lakh acres of land and displace two lakh people, although there are many supporters in the beneficiary state of Andhra Pradesh. Even then, this link is said to be the least damaging and one of the more convenient among all the 30 proposed links.

The Ken”Betwa project in Madhya Pradesh, estimated to be over Rs 10,000 crore, will divert nearly 1,074 million cubic metres of surplus water from the Ken river to the Betwa river basin every year. However, this will require diversion of 5,258 hectares of forest land for the Daudhan reservoir and out of this, at least 4,141 hectares fall in the Panna Tiger Reserve, over 58 sq km being in the core tiger habitat, which as per law is supposed to be a prohibited area. Predictably, environmentalists and wildlife activists have exploded in outrage, citing the damage that will be inflicted on its rich biodiversity. It is also staunchly opposed by the locals, for whom Ken is a lifeline. In response, the ministry of environment, forests and climate change has stalled the implementation till the landscape management plan is given the go-ahead by independent experts. The environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the project has already been slammed for its blatant omissions of endangered species and other wildlife that will be directly impacted. There have been outlandish statements as well – that the canals will provide a shortcut for the fishes to migrate and the reservoirs will help reduce pollution. In March of this year, the environment ministry’s National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) deferred the wildlife clearance for this project.

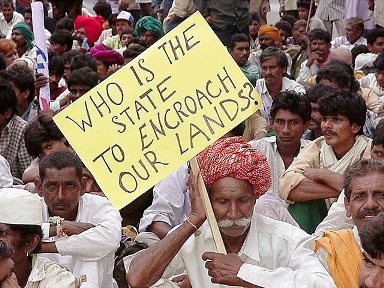

A major issue in the project implementation is cooperation from states with the ‘surplus’ rivers. After all, state governments as well as the local populace will be wont to deny that it has excess water when it is such a basic necessity and is likely to become even more scarce in the near future, thanks in part to rampant environmental damage and climate change. Earlier this year, differences over water sharing between Gujarat and Maharashtra continued to block two river-linking projects, Damanganga”Pinjal and ParTapi”Narmada. Squabbles between states over water sharing are already quite frequent, the Kaveri water dispute being a perfect example. Another unavoidable issue with all mega projects is the question of resettlement and rehabilitation (R&R) for the displaced people. India’s track record in this has been poor at best and projects involving dams have it even worse. There is little reason to believe that ILRP will be any different in this regard.

Squabbles between states over water sharing are already quite frequent, the Kaveri water dispute being a perfect example. Another unavoidable issue with all mega projects is the question of resettlement and rehabilitation (R&R) for the displaced people. India’s track record in this has been poor at best and projects involving dams have it even worse. Past large dam projects show that around 60 per cent of the displaced people are comprised of the Adivasi and Dalit communities. Resettlement and rehabilitation of these half a million displaced people will be a huge challenge and nothing in this country’s history gives much reason for hope.

Further, the project will have to take cognisance of the concerns and legitimate rights of our neighbouring countries, who understandably are wary of this latest fascination of the government. For example, the Ganga Waters Treaty between India and Bangladesh has a clause that the Indian government will endeavour its best to assure that water flows at the sharing point at Farakka are not reduced. It will be a tad difficult to honour that if water is diverted from the Ganga. There is enough bad blood with our neighbours without giving them further ammunition to resent us. Plus, there are legal obligations attached to any transgression of these treaties and international law.

Criticism

Needless to say, plenty of concerns and criticism have been levied against this project. Environmental issues such as impact on surrounding flora and fauna, river pollution, change in the ecological balance, submerging of forest and agricultural land, and dumping of silt from the dams are of major concern. Other more technical issues are related to the fallouts of altering a river’s natural flow and course. For instance, reduced flow can change the shape of existing channels, increasing siltation and sediment deposition, saltwater intrusion in wetlands and coastal areas – all of which will have toxic and irreparable consequences for the local populace and environment.

Massive displacement of people will be unavoidable and the hardest hit will be tribal communities and landless labourers, two sections of the population who have little to gain and the most to lose. Past large dam projects show that around 60 per cent of the displaced people are comprised of the Adivasi and Dalit communities. Resettlement and rehabilitation of these half a million displaced people will be a huge challenge and nothing in this country’s history gives much reason for hope.

Meanwhile, scientists, hydrologists and others worry about potential unintended consequences of reshaping India’s river system, including the possibility of spreading waterborne diseases, disrupting fish migration, and inviting invasive species to travel along channel routes. On the well-touted benefit of hydropower generation, aside from the fact that large dams are themselves controversial, critics point out that the project itself will require enormous energy inputs to lift water across basin boundaries. Real-world efforts to control flooding in the Mississippi and the reduced fertility along the Nile due to damming are used as cautionary examples. Then there are the adverse effects of dams on rivers, explored by a United Nations Environment Programme study in 2001 which, among other things, warned against changing the chemical content of water since it makes it more prone to dirt and pollutants.

Alternatives exist

There are many who insist that more feasible alternatives exist, instead of a pure supply-side monstrosity of a solution that is the ILRP – for instance, demand-driven proposals like better management of existing water resources instead of propping up dams and canals. Costs and environmental impact can be kept low while catering to the needs of the local people. As quoted by a former secretary in the ministry of water resources, ‘a river is not a pipe'” it is part of a discrete, unique ecosystem and any changes to it will have repercussions that need to be detailed out and mitigated. It has been argued that supplemental irrigation through targeted rainwater-harvesting structures, instead of large irrigation projects, can benefit millions of poor, rain-dependent farmers and increase crop productivity. Other proposed solutions are increasing water productivity, artificial groundwater recharge (especially important since groundwater irrigation has easily outpaced surface irrigation in the last few decades), conservation of precipitation within the watersheds or sub-basins, and desalination. Opponents of the project are of the view that till the time a comprehensive assessment of these alternate solutions is done, there is no justification for claiming that interlinking of rivers is the only viable answer for the nation’s water problems.

Exploiting the full potential of rain-fed agriculture, which covers about 60 per cent of crop area but contributes to only one-third of foodgrain production, is another proposed alternative. By increasing this figure, a significant portion of the country’s future food demand can be met. Here it should be noted that most critics of the ILRP recommend a hybrid mixture of all these solutions in lieu of this mega project. Their assertion is simple: these methods are less environmentally harmful, more cost-effective, and infinitely more achievable.

Also, the question remains as to how exactly are surplus and deficit defined, particularly when these qualifiers for a river may change with time. After all, nature and human activities are not static; they ebb and flow much like the river in question. It is essential that future water requirements for both upstream and downstream users be taken into account, especially when consumption patterns are changing by the year. Critics also point out that contrary to projections by the NCIWRD, a substantial portion of future water demand will come from the industrial and domestic sectors – that is, non- agricultural sources.

Past irrigation projects have yielded little or no returns. Since 1991, India has invested more than Rs 1.88 lakh crore in major and medium irrigation but there hasn’t been any substantial addition to the net irrigated area by government canals. Maharashtra, which has the country’s largest concentration of large dams and the least irrigation potential, is a case in point. The 12th Five-Year Plan is also used to denounce the continuing interest in dams whose performance was concluded as ‘dismal’, resulting in the loss of livelihoods and ecological degradation.

Then there is the issue of transparency, or lack of it, in the planning, approval, and governance of this entire mega project. Much like any large government-backed initiative, the ILRP is also fraught with secrecy and lack of specifics. While the government remains gung-ho about it, the fact remains that detailed project reports for most of the linkages are yet to be finalised and made public for scrutiny (detailed project reports [DPRs] of three river-link projects – Ken”Betwa link, Damanganga”Pinjal link and Par”Tapi”Narmada link – have been completed). Even then, it will be anybody’s guess as to how scientific, rational and data-driven this exercise will be. The Ken”Betwa link, being one of the few projects that have had some semblance of documented plans, has already met with plenty of criticism. For instance, here the southwest monsoon meets almost all water demand in the kharif season. However, a good part of the proposed irrigation transfers is for the kharif season itself. The volume of uncertainties and unknowns far outweigh the professed benefits.

Closing thoughts

ILRP as a concept seems logical enough – transfer surplus water to deficient areas. However, in the real world there are a multitude of factors that need to be analysed, considered and accounted for. Attempting to change the very topography of a nation is not something that should be taken up without a rigorous cost-benefit analysis that treats the environment with as much importance as human beings and their needs. The most worrisome aspect of this project is that it has been promoted without a thorough analysis of the overall project impact, not to mention the 30-odd sub-projects that constitute it. Notwithstanding the gargantuan monetary cost (which is likely to balloon up, as the project gets implemented), the economics of this project have not been calculated in a manner that takes into account the social and environmental aspects. It is, then, quite puzzling for the current government to be championing it so aggressively. A cynic might very well contend this to be a charade designed to add gloss to the ‘pro development’ agenda, which is this government’s calling card. After all, it may take decades for the project to be even half completed, and even that will be quite an achievement for a country with such labyrinthine, chaotic and fuzzy processes as India has.

The most worrisome aspect of this project is that it has been promoted without a thorough analysis of the overall project impact, not to mention the 30-odd sub-projects that constitute it. Notwithstanding the gargantuan monetary cost, the economics of this project have not been calculated in a manner that takes into account the social and environmental aspects. After all, one cannot simply ‘fix’ a polluted river, a damaged coastline, or a ruined wetland. Endangered species cannot be easily forced back into a teeming population; nor can trees be replanted to mimic a bygone rainforest. It is, then, quite puzzling for the current government to be championing it so aggressively.

Before further work is invested in it, careful and detailed analysis of every possible economic, environmental and social cost needs to be factored in, along with deep dives into all possible current and future scenarios. Alternate proposals need to be assessed as well and this project should be compared against each one of them. If this sounds laborious, then so be it. A project of this size and scope with the potential to affect every successive generation of this country shouldn’t be taken up unless it is the best of all possible solutions. Grandiose schemes are seductive enough and when the on-paper rationale sounds as simple and feasible as this one, extra caution needs to be employed.

The ecology and biodiversity of a nation is fragile and needs constant nurturing. More importantly, they are one of its true assets and tinkering around with them has serious, irreversible consequences. One cannot simply ‘fix’ a polluted river, a damaged coastline, or a ruined wetland. Endangered species cannot be easily forced back into a teeming population; nor can trees be replanted to mimic a bygone rainforest. While there will be some effect on the environment, it is vital that these be kept to an acceptable minimum.

Instead of harping solely on ILRP, the government would be wise to cull it to a reasonable size (take up those projects that economically and ecologically make sense) and combine it with other local, more eco-friendly and less expensive interventions. On R&R, it goes without saying that a viable, fair, speedy, and transparent process to mitigate the worst of the loss of livelihood and displacement for the affected people ought to one of the highest priorities of this project. The project-affected families (PAFs) should be given multiple rehabilitation options, so that depending on their own unique situations, they are in the best possible position to resume their normal lives with the required comforts and dignity. Unless these basic concerns are addressed, this project will prove to be disastrous, if not in terms of the actual implementation, then for India as we know it.