The 172-acre Kuppam campus is Agastya’s crowning glory and a potential model for educational interventions in India and the rest of the world. It is unique in its core philosophy as well as for the remarkable efforts that have transformed its breathtaking settings, but that doesn’t preclude it from serving as inspiration for other projects that aim to educate children in a way that ignites their minds and creativities, rather than shaping them to fit a predetermined role.

Referred to as its ‘ecology lab’, Agastya’s campus in Kuppam, Andhra Pradesh, has become internationally renowned for its unique model where students are given the freedom to study in labs and in the rich biodiversity of the campus, conducting experiments, observing nature, and learning and discovering in practical ways that pique curiosity and encourage innovation. The campus has science, math, robotics and art studios, a media lab, a bio-discovery centre, a planetarium, herbal and spiritual gardens, acres of playgrounds, and an art and cultural facility. Nearly 700 children visit the campus every day from rural schools in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu for hands-on science education.

Agastya’s success at its Kuppam campus has led to an expansion of its work in the form of over 100 mobile lab vans, labs on bikes, and over 50 science centres which act as a hub for the mobile labs. The vans usually travel to multiple government schools, where instructors explain science concepts to students using lab equipment and models. A single mobile lab covers over 10,000 children a year. The peer-to-peer learning systems include science fairs, college students mentoring government school students, the ‘young instructor leader’ programme where students from government schools are trained to become student-instructors, and the ‘lab in a box’ programme where boxes comprising of elementary aids for explaining science principles are lent to government schools.

A model campus

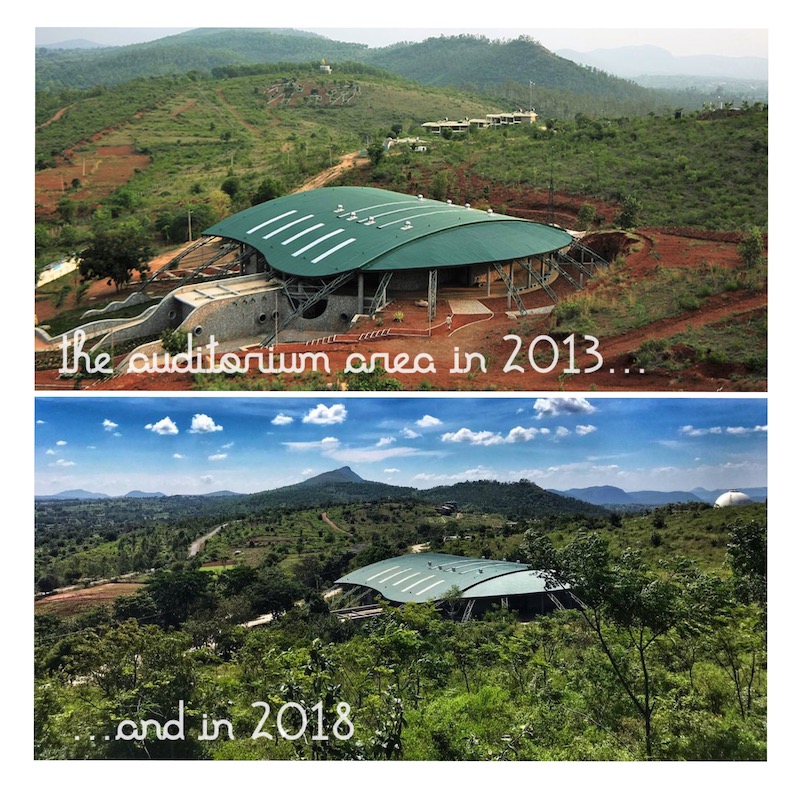

Agastya’s state-of-the-art science education campus for rural children on a 172-acre area in Gudivanka village, Kuppam, has enabled them to become scientists, thinkers, teachers, entrepreneurs, and citizens with a scientific temperament”an urgent need in this country. But its success in pioneering experiential science education isn’t Agastya’s only achievement. The transformation of the hitherto rocky landscape into a thriving ecology lab is a case study in biodiversity regeneration.

This was made possible through Agastya’s willingness to engage experts and, more importantly, use their expertise, exemplified by its collaboration with Yellappa Reddy, former environment secretary for the Karnataka government and a famous ecologist who had restored thousands of acres of land in the Western Ghats.

Agastya had conducted a qualitative research involving in-depth study of the soil, geology and hydrology in 2002 to better understand the ecology of its campus which was initially a barren, rocky land, so that it could design solutions customised to meet the specificities of the landscape rather than the other way round. For instance, Kuppam is in a semi-arid zone with low rainfall and little green cover, a result of decades of deforestation. Bore wells were being dug deeper but this only exacerbated the water problems, drying up the land to the point of asphyxiation.

When Yellappa Reddy surveyed the campus land, Agastya had planted trees like silver oak which were not native to the area. Reddy drew Raghavan’s attention to this and the latter took prompt action by removing the trees. It was then that Reddy decided to come onboard the project to rejuvenate the surrounding landscape. Working with D Subramanyam, who was responsible for maintaining the campus, Reddy worked on several strategies to restore the land to its past glory.

They started by ensuring that the grass was allowed to grow by forbidding cattle grazing and cutting off the grass till it reached a certain size. Aside from check dams to collect rainwater and prevent soil erosion, they dug a few trenches to hold more water to increase the moisture content of the soil. Reddy’s strategy was to minimise interventions, retain the genetic characteristics, introduce plants which are a good fit with the land and animal species that meet the specific requirements of the local food chain, and respect the ecosystem – all part of a holistic eco-regeneration effort, based on science and in-depth data.

These interventions have led to a complete transformation of the landscape. Now it’s no  longer brown and dead but green and thriving. A 2015 IISC report summarised it thus: ‘There has been a total transformation of the campus in the past decade resulting in rocky wasteland being converted into a green campus with rich biodiversity.’ Different kinds of animals, such as a variety of butterflies (so much so that there’s a butterfly park), rabbits, snakes, birds, lizards and spiders are now found prowling through the lush green lands. As Raghavan says, ‘Perhaps our work in revitalising the land of Agastya will be our most enduring legacy.’

longer brown and dead but green and thriving. A 2015 IISC report summarised it thus: ‘There has been a total transformation of the campus in the past decade resulting in rocky wasteland being converted into a green campus with rich biodiversity.’ Different kinds of animals, such as a variety of butterflies (so much so that there’s a butterfly park), rabbits, snakes, birds, lizards and spiders are now found prowling through the lush green lands. As Raghavan says, ‘Perhaps our work in revitalising the land of Agastya will be our most enduring legacy.’

To solve potential water issues, 18 check dams and 8 percolations pits were constructed in 2003 to capture rainwater. The campus generates part of its electricity needs through renewable sources, though there’s scope for expansion. As part of its waste-management plan, biodegradable waste is used as fertilisers for the many gardens and greywater is recycled and repurposed.

The campus’ rich biodiversity was further confirmed by the aforementioned IISC report which conducted field research between 2008 and 2014 to document the flora and fauna of the campus. The study found that vegetation cover had increased from 11.19 per cent to 18.76 per cent from 2001 to 2014. By 2016, the cover is estimated to have increased to nearly 30 per cent. The survey yielded a total of 600 plant species, 86 species of birds of which 20 per cent are migratory and arrive every winter, 49 species of butterflies (many of which are rare and unique), 16 species each of amphibians and rare spiders, 21 species of reptiles, and several mammals”all a testament to the success of the conservation and regeneration efforts.

Another noteworthy strategy employed by Agastya is inviting scientists and experts from various organisations to collaborate, ideate, build syllabus and models, and create modules for teaching and training. Some of the prominent institutions are IISC, Gas Turbine Research Establishment, Atomic Energy Commission, HMT, DRDO, IITs, and University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore. Here scientific expertise is sought and respected, not consigned as an afterthought.

Students have been receiving environmental education at Agastya since 2008. The classroom here isn’t bound by four walls – there’s an ecology lab and the flourishing greenery of the campus. Then there’s the bio-discovery centre that combines indoor and outdoor classrooms, and the learning gardens where students can see, observe, and learn about various plants. It’s no wonder that Agastya’s students and alumni have won several prestigious science awards and participated in multiple science fairs and forums such as Iris National Fair and Google Impact Challenge. The Foundation’s work has been noticed by Stanford Business School and Franklin W Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. Going forward, it will be interesting to see how Agastya balances modern science with traditional knowledge systems such as Ayurveda and Siddhi. Is the latter merely limited to the conceptual gardens or is it going to form a core part of the curriculum?

Students have been receiving environmental education at Agastya since 2008. The classroom here isn’t bound by four walls – there’s an ecology lab and the flourishing greenery of the campus. Then there’s the bio-discovery centre that combines indoor and outdoor classrooms, and the learning gardens where students can see, observe, and learn about various plants. It’s no wonder that Agastya’s students and alumni have won several prestigious science awards and participated in multiple science fairs and forums such as Iris National Fair and Google Impact Challenge. The Foundation’s work has been noticed by Stanford Business School and Franklin W Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts. Going forward, it will be interesting to see how Agastya balances modern science with traditional knowledge systems such as Ayurveda and Siddhi. Is the latter merely limited to the conceptual gardens or is it going to form a core part of the curriculum?

Aside from the campus activities, Agastya is also involved in the community through programmes like iCommunity Mobile Lab where students raise awareness about the local environment to nearby communities, employing locals (90 per cent of the campus staff are native to the area), and distribution of saplings to neighbouring villages.

While Agastya’s impact can be seen on millions of children, it is unclear if this model is scalable due to the enormous amounts of funds, infrastructure, equipment, and staff required. Replicating its success may also prove to be difficult for the same reasons. As anyone who has ever pitched to donors can attest, finding allies and supporters who put their money where their mouth is can often be the biggest challenge. That Agastya has the backing of generous donors and philanthropists is critical to its ongoing success, though like any organisation, it had its fair share of monetary struggles. It may be easier to scale up the mobile lab, science centres, and its many peer-to-peer learning systems. Rolling out the Kuppam education model to other parts of the country will undoubtedly provide a significant boost to the decrepit state of science education in our schools but it will need public funding and private donations and support – material and intellectual “at a massive scale.

That said, capital is one of the key factors; a model such as this needs sustained commitment that doesn’t shortchange long-term impact for short-term wins. Those involved in a project like Agastya need to believe in the underlying philosophy, agree on shared objectives, and fully commit to working towards those goals. Initial field studies followed by regular assessments to comprehend and appreciate the existing project landscape and local needs, meaningful collaborations with experts, ensuring local communities are key stakeholders, constant learning and innovation that speaks to the needs of the target group, and keeping the big picture in mind – these sound easy enough on paper but can be tricky to apply in practice. Agastya has managed this through the dedication of its founders and team; there is no guarantee that other organisations looking to replicate its impact will do so with the same kind of zeal and commitment to the cause.